Secrets of sake: The history and traditions of Japan’s national drink

Sponsored by

Feb 1, 2022 • 5 min read

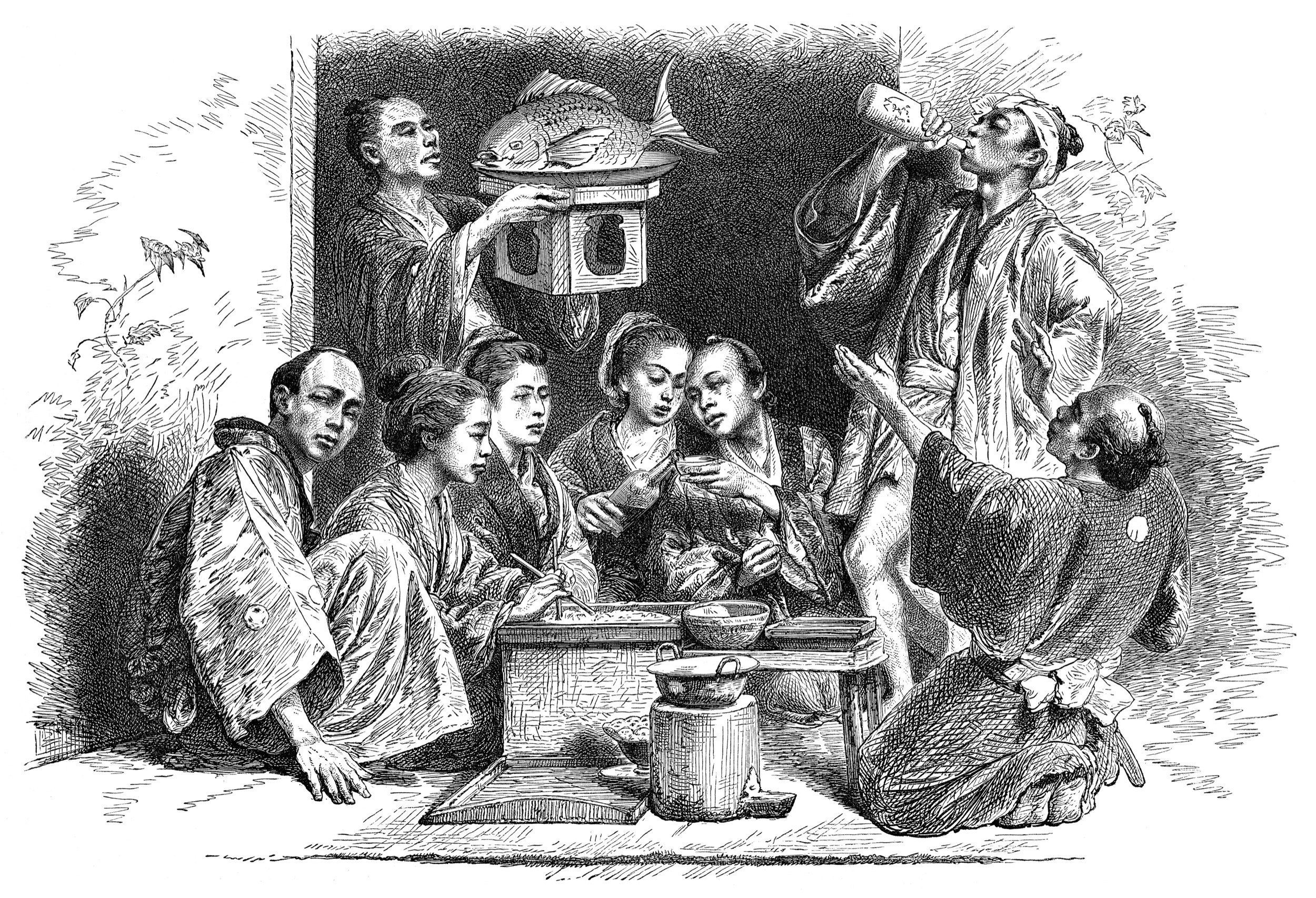

A unique culture has arisen around sake that has earned it a deserved place at just about every important Japanese occasion © Getty Images

Sake has existed for as long as history has been recorded in Japan (and odds are a lot longer). In that time, a unique culture has arisen around this signature drink that has earned it a deserved place at just about every important occasion.

So significant is sake brewing to Japan’s national culture, a traditional method of making sake is soon to be registered as an intangible cultural asset.

Here we’ll discover how rice wine is made, the history that surrounds it, and explore some of the ways sake maintains its cultural, social and historical significance through everyday culture and ritual.

How sake is made

The first step in brewing sake is to prepare the rice. Special varieties of rice suitable for sake making, known as shuzō-kōtekimai, are used and milled to varying degrees to remove excess protein from the outer layer, which affects fermentation.

This process is known as “rice polishing” and in general, the more the rice is polished, the better grade and more expensive the sake. Daiginjō-shu, the highest grade of premium sake, for example, must have at least half of the kernel removed.

The rice is washed, soaked, drained and then steamed in a vat called a koshiki. Cooled rice is then spread out on a long table called a toko, and kōji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) is scattered over it, which converts the starch in the rice into sugar. After two days the kōji is ready and the fermentation process can begin.

Shubo, a fermentation starter, is made when water, kōji, and more of the steamed rice is combined in a vat along with cultured yeast. The fermentation starter is then placed in a tank where more steamed rice, kōji and water is added over three stages, giving the yeast time to multiply in between.

After several weeks, the resulting moromi or “fermentation mash” is pressed to separate the sake from the remaining solids before it is pasteurized, filtered and stored before bottling.

History of sake

The history of sake is believed to date to around the 5th Century B.C.E after rice cultivation was introduced from China. The original and most primitive method of sake production involved villagers chewing rice and spitting it into a communal pot, with the enzymes from the saliva kickstarting the fermentation process.

It was during the Nara period (710-794), however, that sake making became more refined and representative of the techniques used today, including the first documented records of the use of kōji mold. At that time, sake was a drink of the Imperial Court, but later sake production was turned over to shrines and temples, and then commercial brewers.

From the 17th to the 19th Centuries, sake went from localized businesses to an entire industry, with brews flowing into Edo (present-day Tokyo) at an astonishing rate. Trade records show the annual sake consumption at the time was up to 54 liters per capita, 10 times higher than that of today.

In the 21st Century there is a lot of choice when it comes to alcoholic beverages in Japan, but sake’s inherent interconnection with Japanese cultural and religious practices, and a renewed interest in the incredible range of specialty brews that continue to innovate this ancient tradition, ensures its enduring legacy.

Sake and Shintoism

Since ancient times, sake has been used to commune with the gods, as offerings in request or gratitude, and to purify sacred spaces and the people entering them. In fact, sake is referred to as miki in some of Japan’s oldest texts, and was written with the characters for ‘god’ and ‘wine’.

While shrines are no longer the center of sake production, sake is still at the heart of Shinto ritual, so you’ll often find sake barrels at shrines that have been donated by local breweries for the shrine’s many festivals and events.

In exchange, the shrines conduct Shinto rites to ask the gods for the brewers’ continued prosperity. Empty barrels known as kazaridaru or “decoration barrels” donated in gesture are often seen on display, tied together with rope, neatly stacked on shelves or otherwise arranged.

Sugidama, and seasonality

You needn’t look any further than the breweries themselves to see another aspect of sake culture. Before you even set foot inside, you may notice balls of fresh green cedar fronds known as sugidama. These are traditionally hung from the eaves by the entrance to indicate that new sake has been brewed.

Over several months the fronds turn brown, a sign that the sake is now ready to drink. In addition to sake breweries, sugidama can also be found in front of some sake shops.

No country on Earth marks the seasons with the same reverence that the Japanese do. Seasonality is a source of pride that carries into the cuisine and culture, and is intimately tied to changes in the natural world. Sake is no exception, making a notable appearance when admiring the beauty of nature’s seasonal wonders.

The fleeting cherry blossom season, for example, is a time to enjoy sake under the blooms with friends at hanami or cherry blossom viewing parties. Then there’s Tsukimi-zake, sake that is drunk by the light of the full moon during the autumn moon-viewing festival, originally a custom of offering sake to the gods in exchange for a bountiful harvest. And Yukimi-zake or “snow-viewing sake” that is usually consumed hot while admiring the first heavy snowfall of winter.

Sharing sake is also a means of facilitating and solidifying relationships. Whether that’s through conversation over drinks, pouring each other’s glasses, as is custom, or officially marking the beginning of a formal alliance.

In traditional Japanese weddings, for example, the bride and groom will share three cups of sake, each taking three sips in turn from each one to seal their marital bond.

Sake and celebrations

Much like champagne is a sign of celebration in the West, sake is the drink most associated with celebratory events in Japan. On important occasions such as weddings, festivals, store openings, and sports and election victories, a ceremony known as kagami biraki is commonplace.

This involves guests of honor breaking open the tops of wooden casks of sake with a mallet, after which the sake is scooped up with a wooden ladle and served to everyone in attendance, typically in square wooden masu cups. Known as iwai-zake (“celebration sake”), this sake is a means of sharing and reveling in the good fortune together.

Whether you enjoy sake in a formal or casual setting, in reverence of nature or the gods, or in festive celebration, one thing is certain – sake is more than a drink; it’s Japanese culture in a bottle.

You might also like

A sake tour of Japan: Get a taste of the nation’s best nihonshu

Sponsored by Japan Travel & Tourism

As a travel entertainment and inspirational media outlet, we sometimes incorporate brand sponsors into our efforts. This activity is clearly labeled across our platforms.

This story was crafted collaboratively between Japan Travel & Tourism and Lonely Planet. Both parties provided research and curated content to produce this story. We disclose when information isn’t ours.

With sponsored content, both Lonely Planet and our brand partners have specific responsibilities:

-

Brand partner

Determines the concept, provides briefing, research material, and may provide feedback.

-

Lonely Planet

We provide expertise, firsthand insights, and verify with third-party sources when needed.

Take your Japan trip with Lonely Planet Journeys

Time to book that trip to Japan

Lonely Planet Journeys takes you there with fully customizable trips to top destinations – all crafted by our local experts.