Is there an appropriate age to bring children to visit Auschwitz?

Jan 30, 2022 • 5 min read

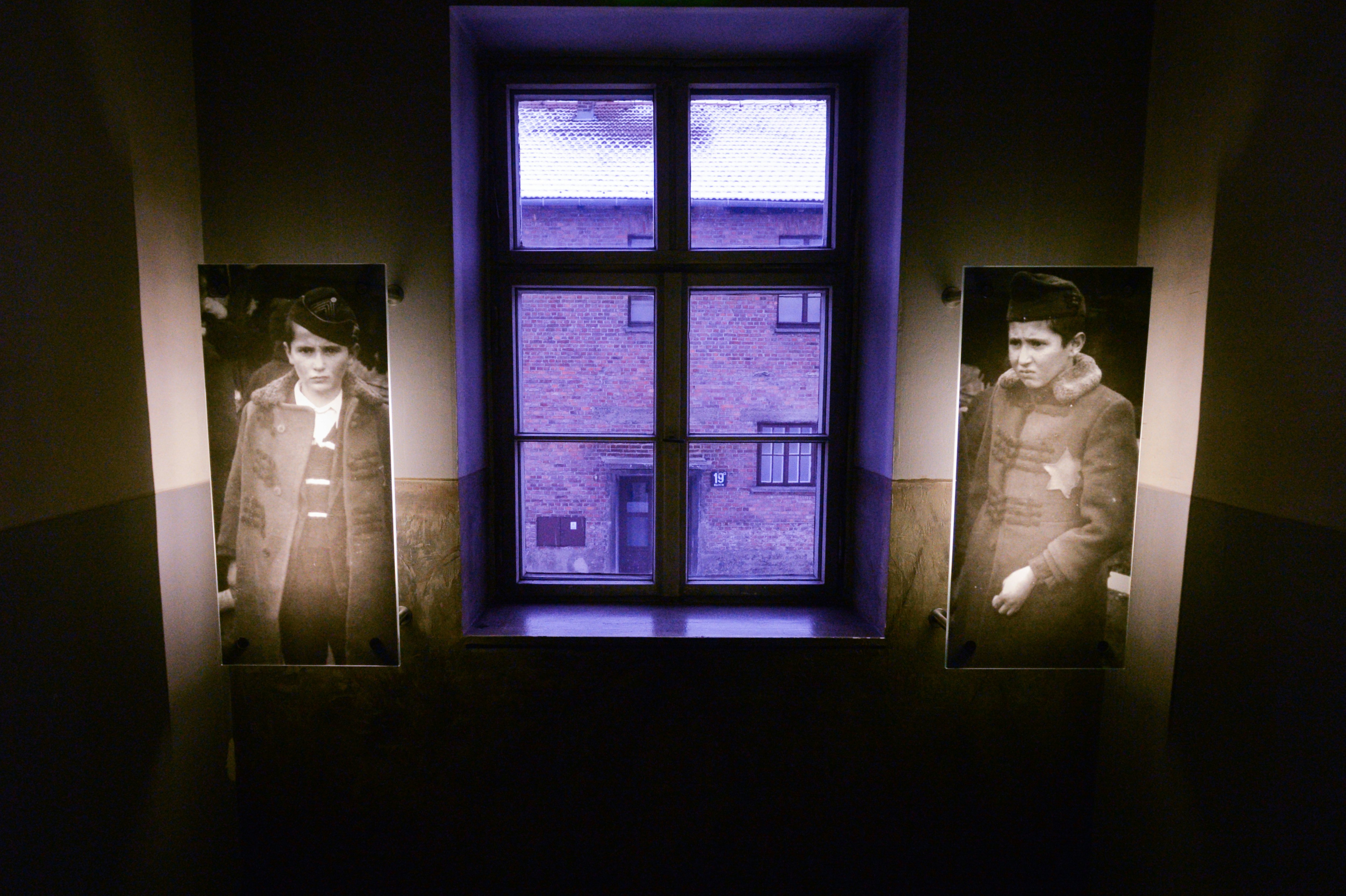

Understanding the Holocaust doesn’t come without distress © Ulrich Baumgarten via Getty Images

This week saw Holocaust Memorial services taking place around the world, as we marked the 77th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz Birkenau concentration camp by Soviet troops.

Since 1945, the former concentration camp has become a highly-visited historical site, with a record 2.15 million people taking the tour in pre-COVID 2018, many of them teenagers. But is there a ‘right’ age to bring a child or young person? Are children sometimes too young to be exposed to the horrors of the Holocaust? Official guidelines from memorial staff recommend that those under 14 do not visit. But this is just a recommendation, not a rule.

The remarkable plasticity of the teenage brain means there is an opportunity during these years to fundamentally affect, for good or ill, their understanding of the world. If we take time to expose young people to the kind of profound experience that is Auschwitz-Birkenau, there is great hope that they will form an impression that will stay with them; an understanding of the horrors humanity is capable of and a determination to be vigilant against them.

This seems to be generally recognized, with many secondary schools organising trips. In the UK, the Department for Education has funded a programme since 1999, with over 40,000 students and teachers taking part in the Holocaust Educational Trust's, Lessons from Auschwitz Project. This is based around the premise that 'hearing is not like seeing', and aims to increase knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust for young people.

What to expect on a visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau

“I wasn’t scared to go, I was interested,” says 18-year-old Harry O’Donoghue, who was 16 when he visited Auschwitz-Birkenau with his mother and grandfather. “We had studied the period at school, and I had an idea of what to expect.”

Of the two camps, Birkenau left a lasting impact on him. “The huge, grey buildings, the iron fences, the guard towers. Auschwitz didn't look as I had imagined it," he adds. “In essence, it is a vast field, with wooden shacks and barbed wire. Trying to imagine 750,000 people here was difficult. In Birkenau, looking at rooms full of shoes, of human hair, spectacles, that brought the scale of it home more.”

He found the suitcases and luggage the most distressing of all. The cases have labels on them, with names and dates of birth visible, so it's possible to calculate the age of the person to whom they belonged. A number of them are left open; seeing a pair of neatly folded pyjamas and a teddy-bear, packed by a three-year-old child, really affected him.

Understanding the Holocaust doesn’t come without distress. Teenagers are highly emotional, there is a chance that some will feel overloaded, helpless in the face of the greatest monument we have to inhumanity and evil. When asked if she had worried about taking him, however, Harry O’Donoghue’s mother, Deirdre, said no. Harry has always been an avid reader of history and he knew a lot about the period. The pair were also able to talk about it afterwards. Her father – now in his 80s – had always wanted to visit, too.

Emily Gleeson and a small group of classmates were warned that they might be overwhelmed when they visited Auschwitz-Birkenau.

For 14-year-old Emily, the impact was immediate: “We prepared before going, including watching movies like Schindler’s List, to get some idea of what we would see, which was good.” She was also taken aback by how real everything felt – Auschwitz is not dressed up, or a museum; things have been kept as they were.

Most distressing for her was the room full of hair and personal belongings: “All those shoes, that was very disturbing” she says. “Suddenly, the scale becomes more understandable. It’s impossible to imagine one million people, but when you see a room with suitcases piled high up to the ceiling, you can begin to get an idea.”

Donna Gawell, a historical novelist, took her two daughters to Dachau when they were 11 and 15. They later visited Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Building children into educated future voters

“It was a very profound visit for both [of her daughters] and I did little preparation with them as it was also my first time visiting," she says. "My daughters really appreciated the visit and for the next few years, used that experience as their topic for writing assignments in English and Social studies.”

Her youngest now reports that she is grateful for the trip, although she doesn't remember much. Donna believes it strengthened her and rendered her a more compassionate person. While Donna's daughter was shocked, she also says she wasn’t frightened or terrified and didn’t have bad dreams or anxiety about what she saw.

Donna continues: “I wouldn’t necessarily ask if my child wanted to go; I would make the decision for them. Most kids don’t realize what a unique experience they will have. Taking your child to Auschwitz is a gift to build them into a strong, compassionate, and educated future voter and citizen.”

Editor's note: during COVID-19 there are restrictions on travel. Check the latest guidance before departure, and always follow local health advice.

Not everyone welcomes young people at what is a place of solemn witness, sometimes of family trauma. There are stories of noisy groups taking selfies and behaving with a lack of respect. This may be the result of an inability to deal with the emotions raised, but it certainly comes across as callous. Emily's teachers were very clear with her and her classmates before they went about what was appropriate behavior, and the whole group stayed quiet.

Did the trip change the way she sees the world?

“I’m glad I went,” says Emily. “It was an eye-opener. It has changed the way I think – knowing that people can do that, can think like that.”

For Harry, it was definitely worth going: “It made me feel very sad – the coldness of it. Those places could have been built by robots. There was no human feeling in their design, and so obviously those who created them didn't think of the people they kept there as human. But it was important to see that.”

You may also like:

The 70,000 small tributes to Holocaust victims that most people don’t notice

Top 10 things to do in Poland